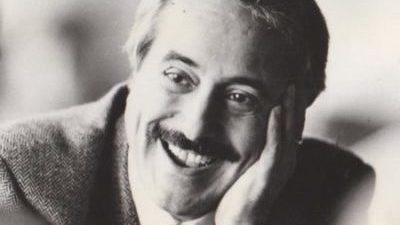

On the 23rd of May 1992 Judge Giovanni Falcone was killed in the Capaci massacre together with his wife Francesca Morvillo and the police escort agents Vito Schifani, Rocco Dicillo and Antonio Montinaro. About 500kg of TNT positioned on the A29 motorway at the junction between Isola delle Femmine and Capaci were blown up when the car passed.

The terrible attack was directed to eliminate one of the best servants of the State, the one who had hit the mafia hard in the framework of the maxiprocess of Palermo, and continued to represent a danger because of his pioneering investigative ability and his tireless determination in contrasting the mafia phenomenon.

In the Judiciary, the responsibilities of Cosa Nostra were confirmed with the convictions of prominent mafia bosses and the material executors of the criminal organization. However, 28 years after that massacre, some unresolved issues still remain. There was, in fact, a broader convergence in the elimination of Giovanni Falcone, first, and of Paolo Borsellino, later. Professor Nando dalla Chiesa called it a two-stage massacre, because there was a link between the massacre of Capaci on 23rd of May 1992 and the massacre of Via d’Amelio on 19th of July of the same year.

The judges had certainly been targeted by Cosa Nostra for some time, given their investigative efforts in the anti-mafia pool that led to the maxiprocess established in 1986 and strongly wanted by the two. On that occasion, also thanks to the statements of the justice collaborator Tommaso Buscetta, it was possible to identify the unitary and vertical structure of Cosa Nostra, which Falcone had already perceived during Rosario Spatola’s trial. Falcone himself, in the book-interview “Cose di Cosa Nostra” realized by Marcelle Padovani, affirmed that Buscetta had succeeded in giving them a fundamental key of the criminal organization code. The maxiprocess ended in first degree on the 16th of December 1987, with an interminable list of convictions: in total, there were 346 convictions – among which, 19 life imprisonment and 2665 years of prison altogether. The accusatory system also held up in second degree, although with some mitigation.

By the time the trial reached the Supreme Court, Giovanni Falcone was part of the Ministry of Justice as Director of Criminal Affairs, with the task of coordinating the fight against organized crime at the national level. Falcone urged the former Minister of Justice, Claudio Martelli, to introduce the rotation of the Court of Cassation chambers in order to avoid contamination. The choice of the judges for the Maxiprocess was made by drawing, to avoid the actions of the president of the first section, Corrado Carnevale, also known as the ”sentence-killer”. In fact, in his career, he ordered the invalidation of numerous mafia sentences thus facilitating the release of mafia criminals.

The trial ended on the 20th Jof anuary 1992 with an unprecedented sentence. All the convictions were confirmed and the attenuations sanctioned on appeal were removed.

The vengeance of Cosa Nostra was expected, but what worried the mafia and their network of relationships was mainly what Falcone and Borsellino could still accomplish.

Falcone’s legacy

Judge Falcone, during his time at the Ministry of Justice, promoted since the beginning of 1991 the creation of structures that today are fundamental in the fight against mafia-type organized crime in Italy and that are internationally envied. Taking advantage of the experience of the anti-mafia pool in Palermo, conceived by Rocco Chinnici and then put into practice by Antonino Caponnetto with the aim of centralizing the investigations on the mafia, Falcone proposed the setting up of the national coordinating centre for investigation and exchange of information related to the mafia phenomenon.

Thus, the National Anti-Mafia Directorate (DNA) was created, with the purpose of horizontal investigative coordination and simplifying the communication between the District Anti-Mafia Directorates (DDA). The Anti-Mafia Investigative Direction (DIA), composed of police forces is a proper operative pole in charge of judicial investigation activities, was added to these bodies.

Falcone’s vision went beyond the national borders. In fact, he was convinced that the fight against the mafia had to be pursued with cooperation at a global level. He was the promoter of an international conference for organizing a multilateral approach in the fight against organized crime. There was a need for adequate legislation to tackle the mafia phenomenon that was now affecting institutions and societies worldwide. Falcone’s idea then became reality with the international conference in Naples in 1994 and the subsequent adoption of the Palermo Convention on transnational organised crime in 2000.

At a national level, however, Falcone’s initiatives as Director of Criminal Affairs were also criticized within the judiciary itself, as there was fear of an excessive centralization of powers which, in reality, never occured. The figure of the National Anti-mafia Prosecutor was introduced and soon Giovanni Falcone became the ideal candidate. This perspective upset many and above all the mafia and the corrupt economical and institutional circles. They would have had to face the most competent judge in the fight against the mafia as the new Super-Prosecutor and this time not only from the offices of Palermo, but on a national scale. This frightened Cosa Nostra, just as it frightened them the fact that after the Capaci massacre, it could have been Paolo Borsellino, Falcone’s ”twin” to hold that position. That is the convergence of interests that led to the elimination of the two judges in the so-called ” two-stage massacre”.

During the period at the Ministry, Falcone had conceived a series of instruments to combat the mafia which included, in addition to the Super Prosecutor’s Office, also: a new regulation on collaborators of justice; the institution of hard prison for mafia bosses – among which the structures of Pianosa and Asinara and the obligation for banks and financial institutions to report suspicious operations concerning money laundering.

We often hear about the ”Falcone Method” to underline his capacity for investigation. In fact, we remember his intuition to ”follow the money”. That means that it’s necessary to follow the financial flows to understand the strategies of economic expansion of the mafia in Italy and beyond the border, through judicial investigations and preventive investigations. Falcone was innovative because he did not remain anchored to the codes, but understood the need to develop another type of competences.

But he went even further. To understand the mafia, it is not sufficient to follow the money. Falcone underlined also that the mafia is a phenomenon of power. The mafia is part of a social system and relies on more or less aware alliances. It controls the territory through the use of violence and carries out illicit activities, feeding this system and reinforcing itself with the money it circulates in the economy.

There were those who claimed already in the 80’s that the mafia should be sought in the circuits of high finance in international centres like London, Zurich and Frankfurt – and Falcone answered that the head was located in Palermo. Because the mafia evolves while remaining itself.

It was Falcone who then introduced the idea of the external collaboration in the Mafia association. The magistrate was deeply convinced that without the connivance of professional figures and without the help of the so-called “small and big singers”, the mafia would not be able to achieve its goals. This concept was also expressed by Professor Nando dalla Chiesa in the book written with Pino Arlacchi “La palude e la città” that ”the strength of the mafia is outside the mafia” (1987). Therefore, he underlined the necessity to focus on external support to the mafia, because that’s what allows it to be victorious.

To counter the mafia phenomenon, it is necessary to study it carefully, and Falcone understood that it was necessary to learn to think and reason like them, to get into their logic of action and analyze their behaviour.

The criticisms and difficulties

Today he is recognized and remembered as one of the highest symbols of the fight against the mafia, but during his life Giovanni Falcone was subject to attacks of all kinds. There was a part of society, press and even the judiciary that criticized him harshly. Among the various epithets that were given to him was that of ”sheriff judge”; he was then, according to the occasion, accused of being a friend of this or that political party; and after the failed attack of the Addaura against him, it was even claimed that he had organized it alone to obtain visibility.

What indirectly struck him was also the controversy that arose from Leonardo Sciascia’s article on the “Antimafia professionals” of ’87, which had as its explicit objective Paolo Borsellino and his designation as Prosecutor of the Republic of Marsala for merit instead of the classic criterion of seniority of service. There was controversy about the fact that ”nothing is worth more, in Sicily, to make a career in the judiciary, than taking part in mafia-type trials”. The detractors of Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino took the chance and felt even more legitimated in their attacks on the two judges.

In that context of envy, calumny and discredit, Giovanni Falcone’s professional career was also affected. When Antonino Caponnetto retired for health reasons, Falcone was seen as his natural successor as head of the Investigation Office in Palermo, but the Superior Council of the Magistracy (CSM) preferred Antonino Meli (14 votes for Meli, 10 for Falcone and 5 abstained), an older colleague but without the slightest experience in mafia trials. The consequence was the progressive dismantling of the anti-mafia pool.

As her friend and colleague Alessandra Camassa and his colleague at the time of the anti-mafia pool Leonardo Guarnotta remember in the documentary “Uomini Soli” in 2012, every time Falcone applied for a position – for which he was obviously the best possible candidate – he was always rejected. He could have been recognized for what he had shown in the fight against the mafia and instead he was never promoted. Immediately after his rejection as head of the Investigation Office, Domenico Sica was preferred as High Commissioner for the fight against the mafia and in 1990 he did not obtain the position of advisor to the CSM. Falcone then decided to go to Rome to the Ministry of Justice to do what he no longer felt he could do in Palermo.

“Their ideas walk on our legs”

At a conference on the occasion of the thirtieth anniversary of the maxiprocesso of Palermo, the former magistrate Leonardo Guarnotta claimed that what Falcone and Borsellino left us is ”a heritage rich in teachings, gestures and words, behaviors, memory”. The testimony of their sacrifice and commitment gives us courage. Their lives have been characterized by important victories and burning defeats, but they have not surrendered to difficulties and have always been promoters of change. They were the highest servants of the state and they did it for the sake of legality.

Giovanni Falcone taught us that the mafia must be studied, understood and finally fought. There is a need for professional rigour. You can’t tackle real crime professionals with amateurs. The best and most competent people must fill the positions of responsibility, otherwise this fight will never be won.

Their teachings concern all of us. The legacy they have left us is our cultural heritage.